During the past year, there has been a lot of controversy over the DSM-5, its upcoming publication, and its proposed revision of the diagnostic criteria for autism spectrum disorders.

By merging all autism spectrum disorders into one, Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), the DSM-5 has freaked out different people for the same reason, that being who will be diagnosed or not diagnosed according to the newer, stricter criteria within.

Some adults are worried that they will not meet the full criteria to be diagnosed with ASD.

Some parents are worried that their children will not meet the full criteria to be diagnosed with ASD.

Some adults are worried that they will be too high-functioning to be diagnosed with ASD.

Some parents are worried that their children will be too high-functioning to be diagnosed with ASD.

Some researchers and clinicians tell everyone not to worry, that everything will be A-OK, and that the DSM-5 will diagnose just as many children and adults as does the DSM-IV.

Some researchers and clinicians tell everyone to worry, that everything will not be A-OK, and that the DSM-5 will not diagnose many many many children and adults diagnosed or diagnosable by the DSM-IV.

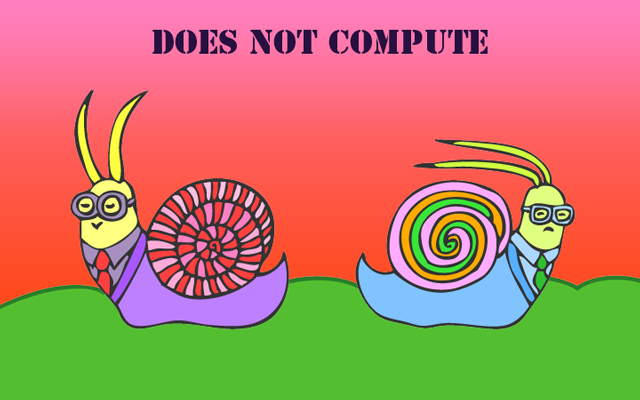

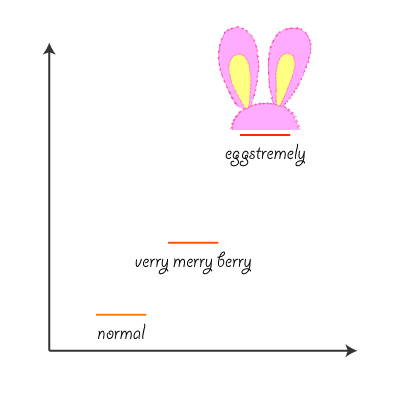

Studies are done, and papers are published, and some show the former, and some show the latter, and there is no general agreement over what will happen when the book is published and the criteria applied. On opposite sides of the DSM-5 Divide, the researchers snipe at each other, criticizing the methodology here and the agenda there, while the people affected by the changes, the autistic adults and children and the families of autistic children and adults, are freaked out and have no idea what or who to believe on an issue that is verry merry berry important to them.

Lost in the DSM-5 Diagnosis Rate Debate have been the criteria themselves, the proposed revision of the diagnostic criteria for ASD that is causing so much controversy in the World of DSM-5 Discord.

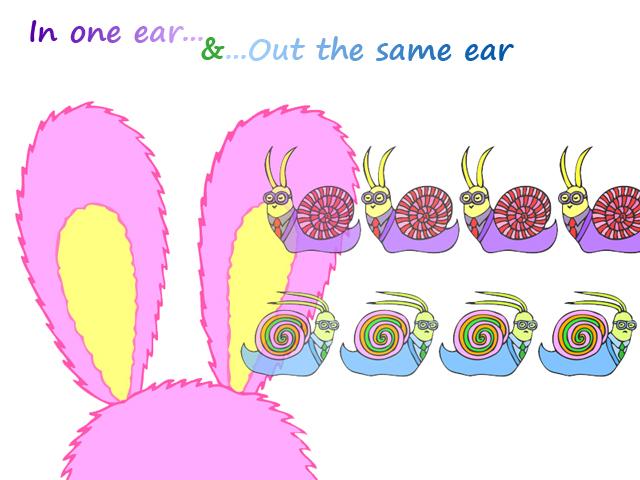

I don’t care about the DSM-5 Divide, Debate, Discord. My theory of mind is not good enough for me to understand these things.

I only care about the criteria themselves. My theory of mind, my autistic theory of autistic mind, is good enough for me to know what autism is, and whether the criteria will be good for diagnosing autistic people with autism and not diagnosing non-autistic people with autism, which are what the diagnostic criteria are made to do.

Here is the link to the criteria: DSM-5 ASD

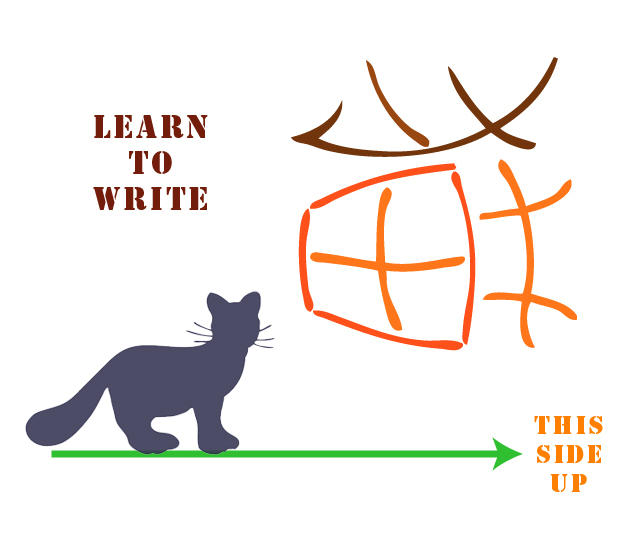

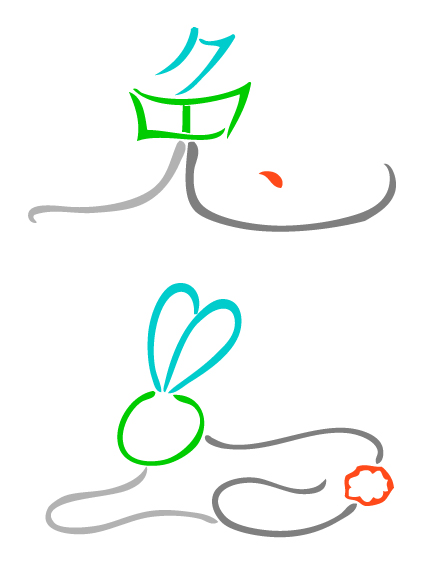

Here are the criteria in HooomanSpeak, the profile of an autistic person from the perspective of a typical person who knows a little about autism from the outside, e.g. the clinician diagnosing autism, e.g. the researcher investigating autism:

(A) Deficits in social interaction and communication, meet three of three:

(1) Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging from blathering on and on and on about the same indescribably boring things and not STFU-ing when I make gooogly eyes at you to STFU to all-walkie-no-talkie when I call your name and make gooogly eyes at you to walkie-talkie to me (OMG! Why can’t you just act normal for once?)

(2) Deficits in non-verbal communication, ranging from not molesting my eyeballs with your eyeballs in a socially appropriate manner to not molestng my eyeballs with your eyeballs at all (OMG! Why can’t you just act normal for once?)

(3) Deficits in development of relationships, ranging from not knowing how to make friends or friends with benefits and suck up to people for selfish personal gain to not knowing that there are such things as making friends or friends with benefits or sucking up to people for selfish personal gain (OMG! Why can’t you just act normal for once?)

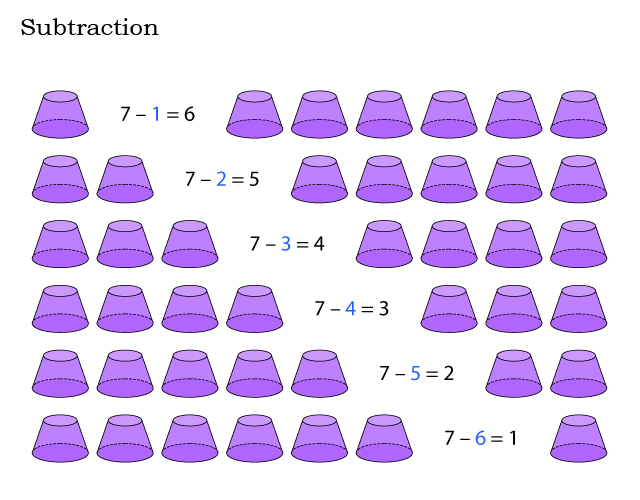

(B) Restricted and repetitive behaviors, meet two of four:

(1) Stereotypies, e.g. echoing with I say and doing it lots lots lots to annoy the begeebus out of me, e.g rocking back and forth and doing it lots lots lots to annoy the begeebus out of me (OMG! Why do you act so autistic all the time?)

(2) Routines and rituals, e.g. going to the same boring old people’s park for five minutes a day everyday, rain, snow, hail, frogs, locusts, plague, and nukular reactor and/or missile catastrophes, to do nothing there, because there is nothing to do there, but your parents made the mistake of taking you there this one time when they were suckers for your gooogly eyes that were not ackshuly gooogling at them to take you to the park that they falsely believed that you desired them to take you to and came to suffer the long-term consequences thatof, poor foolish hooomans who would have been driven insane by you, had they not been insane to begin with, e.g. keeping each and every object in the same location and orientation at all times and freaking out if those are changed at any time by any amount (OMG! Why do you act so autistic all the time?)

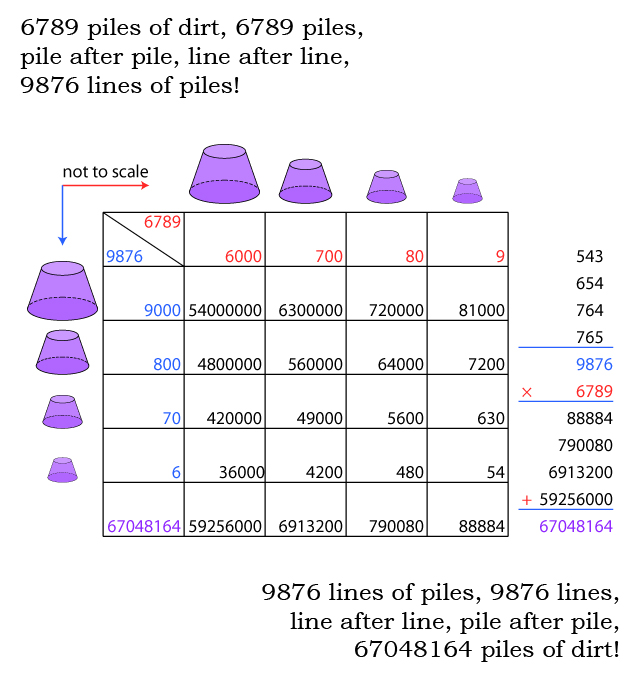

(3) Special interests, e.g. pursuing the same nevar-evar-ending dirt- and block-building projects with laser-like intensity and focus for hours and hours and hours day after day after day, e.g. poring over the same indescribably boring doorknob model numbers with laser-like intensity and focus for hours and hours and hours day after day after day (OMG! Why do you act so autistic all the time?)

(4) Sensory abnormalities, e.g. going berserker whenever the lights are turned on, e.g. going berserker whenever the phone rings, e.g. going berserker whenever the wind blows on your face, e.g. berserkedly smelling each and every object and hoooman in your path, e.g. developing a berserk taste for things that are not food (OMG! Why do you act so autistic all the time?)

From the perspective of an autistic person who knows a lot about autism from the inside, the criteria read more like this:

(A) Lack of typical social brrrainzzz

(1) Lack of typical social brrrainzzz (I ain’t gotz no normal brrrainzzz, nope nope nope)

(2) Lack of typical social brrrainzzz (I ain’t gotz no normal brrrainzzz, nope nope nope)

(3) Lack of typical social brrrainzzz (I ain’t gotz no normal brrrainzzz, nope nope nope)

(B) Awesome autistic things that I ain’t lackz

(1) Awesome autistic things that I love to do and can’t do without (They will have to spoooooool these things out of my brrrainzzz through my nostrils if they wish to rid me of them, yep yep yep)

(2) Awesome autistic things that I love to do and can’t do without (They will have to spoooooool these things out of my brrrainzzz through my nostrils if they wish to rid me of them, yep yep yep)

(3) Awesome autistic things that I love to do and can’t do without (They will have to spoooooool these things out of my brrrainzzz through my nostrils if they wish to rid me of them, yep yep yep)

(4) Awesome autistic spidey senses that make me a good (a) vampire, (b) eavesdropper, (c) barometer, (d) shark, and (e) vampire (I will suck out their blood and bite off their limbs if they try to spoooooool any of the above above above out of my brrrainzzz through my nostrils that will suck in the air that I will need to rid me not of them, but them other them, harharhar)

In addition, two other criteria must be met for an autism diagnosis to be made:

(C) Be autistic since early childhood.

(D) Have impairments in functioning caused by being autistic.

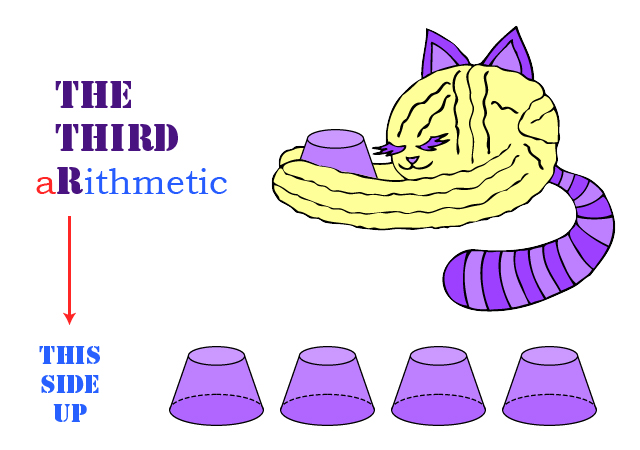

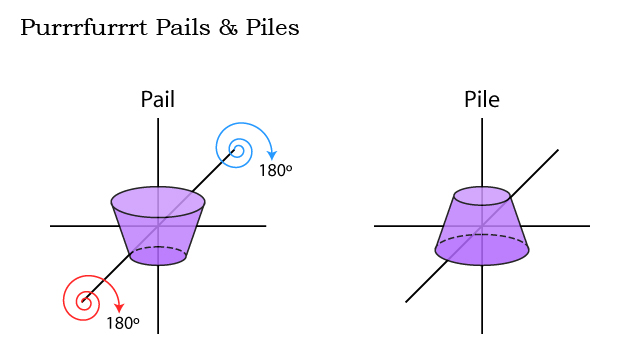

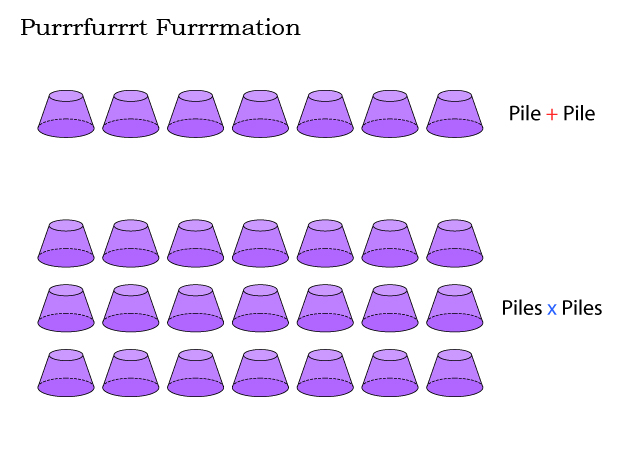

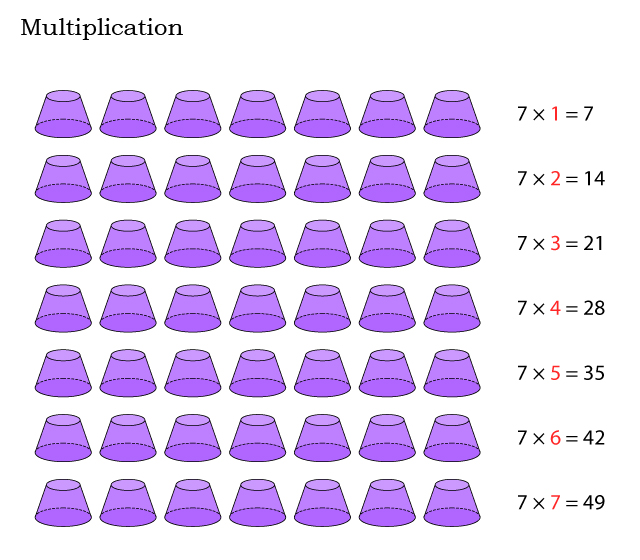

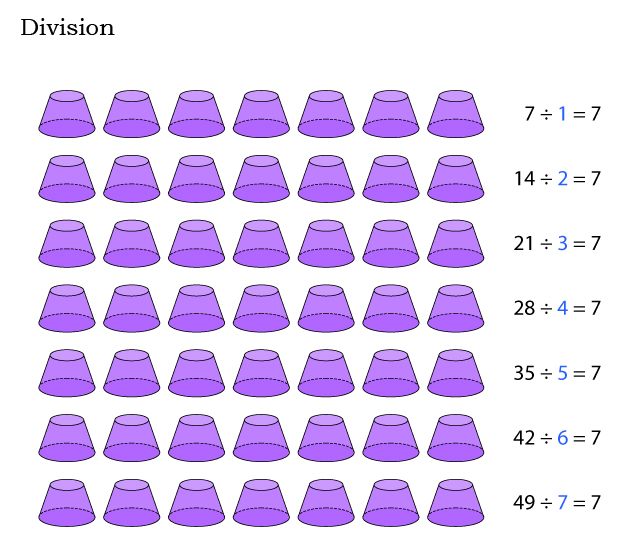

In multiplication, the diagnosis also comes with a severity level:

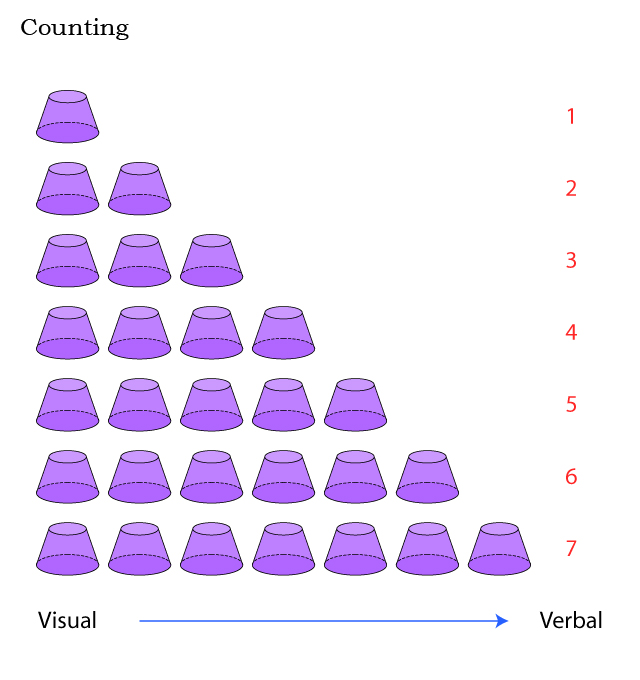

Level 1: Requiring support (DSM-Speak is so vague that no one knows what this means)

Level 2: Requiring substantial support (DSM-Speak is so vague that no one knows what this means)

Level 3: Requiring very substantial support (DSM-Speak is so vague that no one knows what this means)

DSM-Speak is so vague that no one knows how the severity levels will apply to real live hooomans, but what is not vague is that there will have to be some identifiable impairments in functioning and some identifiable accommodations for those impairments for an autism diagnosis to be made for a real live awesome autistic hoooman.

So what is so super duper wrong with the DSM-5 to cause so much Divide, Debate, Discord?

In my opinion, nothing is super duper wrong, nothing so super duper wrong to cause so much Divide, Discord, Debate.

The purpose of the DSM-5 is to define what autism is at the behavioral level, the only level at which we currently know enough about autism to be able to define it at all. We don’t know much about autism at the cognitive level or the neurobiological level or the molecular and cellular levels, but in order to know moar moar moar about these other levels, we have to do what we currently can, which is to define what autism is at the behavioral level, definitely and definitively, like how an autistic person acts, and how an autistic person acts differently from a typical person, and how different autistic persons act differently from each other, so we can figure out the moar moar moar interesting things, like how an autistic person thinks, and how an autistic person thinks differently from a typical person, and how different autistic persons think differently from each other.

As a definition of autism, the DSM-5 criteria for ASD are fine. They are about as fine as any other criteria that I have ever read. In my opinion, the criteria present a profile of an autistic person from the perspective of a typical person, require autistic traits that are fundamental to autism, and recognize that there is a variety of expression of those traits, a spectrum starting and stopping with the difficulties experienced by real live autistic people in a world not designed by or for them and the supports for those difficulties that can help moar moar moar of us do moar moar moar of what we need and want to do in our lives.

The DSM-5 definition of autism makes verry merry berry much sense to me, and it is verry merry berry close to the original definitions of autism by Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger, the ones that describe awesome autistic children in a way that makes sense and rings true to an awesome autistic child like me.

What will happen to the rate of diagnosis when the newer, stricter criteria are applied is unknown to me, but what I do know is that there is nothing super duper wrong with the criteria themselves.

My theory of mind is not good enough to understand the DSM-5 Divide, Debate, Discord. All I know is that criteria themselves make sense and ring true, based on what I know about autism from learning about it the way the clinicians and researchers learn about it, and understanding it the way that only an autistic person ever could.

To me, the DSM-5 does a good job of defining the truth of autism for the purpose of diagnosis. The consequences of the truth, I have no idea what they will be. Perhaps they will not be a big deal, as some say, and the rate of diagnosis will not change, not change much at all. Perhaps they will be a big deal, as some say, and the rate of diagnosis will drop, not necessarily the big bad snake-scaled fork-tongued monster that it has been made out to be.

But in my opinion, and from my perspective, the unknown consequences of the truth should not stand in the way of the truth itself. I support the DSM-5, and I think that the book should be published and the criteria applied. I think that the DSM-5 definition of autism, just autism, is superior to the DSM-IV definitions of Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder, and Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified. In the DSM-5, I particularly support the diagnosis of autism and autism alone, no more Autistic Disorder (the Big Bad Autismism that will ruin your life and the lives of everyone around you) or Asperger’s Disorder (the Special Autistical Autistican Syndrome that is the same as autism to some who have it and totally different for others who do too) or Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified (the Confusing-B-U Confused-R-Us Catchall that is some kind of autism for some who have it and totally not for others who do too) to classify and class autistic people into categories that they may or may not fit, in which they may or may not get the help that they need.

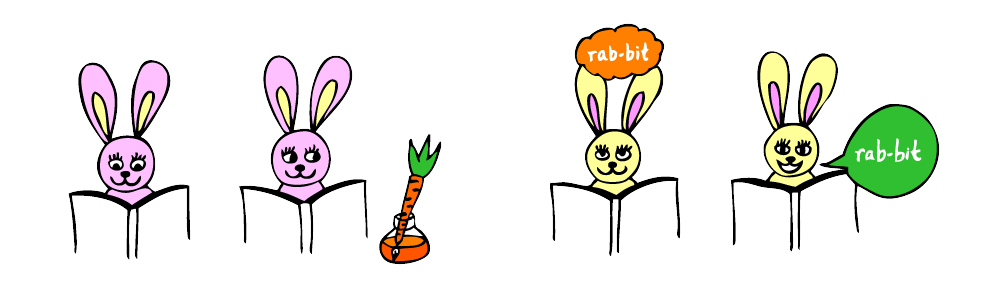

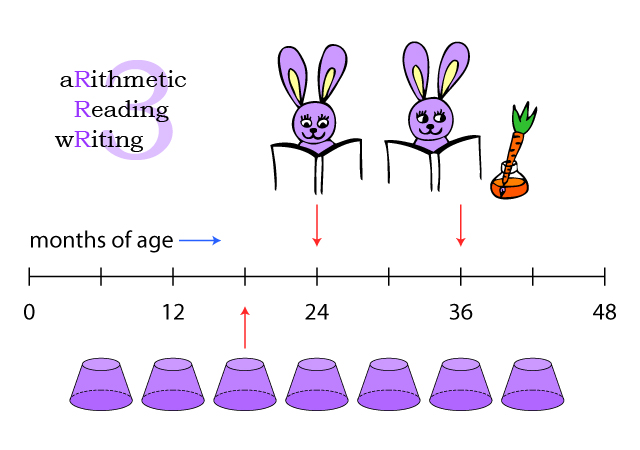

In the DSM-5, autistic people are just autistic, strong, simple, and pure. The severity levels do run the risk of putting people into boxes, Levels 1, 2, or 3, but that risk can be reduced by recognizing that autistic people can move from one level to another as they grow up and learn things. Autistic children diagnosed at two-and-a-half at Level 3 can level up into autistic adults of twenty-and-a-half at Level 2, then thirty-and-a-half at Level 1. That is the true nature of true autism, that autistic children grow up and learn things, do more and need less, leveling up. If these are not what an autistic child is doing, then that autistic child should be taught and supported to do them, to grow up and learn things, do more and need less, leveling up.

Towards these goals, I hope that the DSM-5 will do a lot of good and not much bad at the first step, the diagnosis. To me, the criteria make sense and ring true, as they do to a lot of other autistic people too. Right now, that is all I care or can care about, the truth, and all I can do is to sit back, relax, and pop things, all food items, into my mouth, to handle the good and bad of it.